Study Card

Cheat Card

Snitch Card

Gossip Card

Strategic Diagram.

Each card has various potential interactions with other cards.

By Jiaxi, Maddy, Eli, Alex, Jake

Abstract

Study Group has players take the role of groups of students trying to do well on a test. The goal is to score as high as you can each round by playing one of the four actions in your hand. However, the points you get depend on what other people do and if you work as a group.

The actions you can take are represented by cards in your hand, and each turn you must choose two that you might play as you reveal them to everyone. You may study for the test which is guaranteed a point, you may cheat which gets you 2 points alone but extra points for cheating with somebody else, you may snitch on the other people on your group for cheating which can grant you a point per cheater, or you can play the difference card which grants a point for each of the different actions played by the other players. The two cards from your hand are placed face down, and then one is revealed while forming groups, then the other is shown before placing the action you want forward. The actions are then revealed, and the points are distributed, represented by tokens, and the cards played are discarded. Get the most points after everyone plays all their cards, and you win!

Materials

- A standard deck of cards

- 20 Tokens to represent points

Rules

Set up:

- This game is designed for 4 to 6 players.

- You win by reaching the highest score by the end of the game.

- For each game, you start with 8 cards with 2 of each suit. The number/rank on the card is irrelevant in this game. The only thing matters is the suit.

- Each suit stands for a different action. Action includes: Study (Spade), Cheat (Diamond), Snitch (Club), and Troublemaking (Heart). See detailed explanation for each actions in the “Action and Group” section.

For each turn:

- You starts with picking any two cards from your hand. These two cards indicate your potential actions for this turn. After you pick the cards you want to play, you put down these two cards face down in front of you.

- After everyone has put down their cards, you then reveal one of the two cards publicly.

- Once every player has shown one of their cards, the floor is open for “grouping.” You can freely communicate with other players to reach cooperation and form a group. Once a group is created, it becomes solid and unbreakable for the turn. There could be multiple groups in one turn, and there could be as many players in one group as you want. You can not form a group by yourself.

- All players reveal their second card after all groups are formed (See “Action and Group”). At this point, you can communicate and try to convince other players about their final move, but you cannot join or leave a group anymore.

- Then, all players would take back their two cards and decide one final card they would like to play. Once you make your mind, you have the card face down placed in front of you.

- After all players put down one card, all players reveal their card and calculate their score. You should take the same number of tokens with your score from the box and place in front of you.

- The card you have played would go to the trash pile. You cannot use it for the rest of the game. The card that you have not played goes back to your deck. You can always play it the next time. By then, all player’s hand reduce by one card, and a new turn begins.

Action and Group:

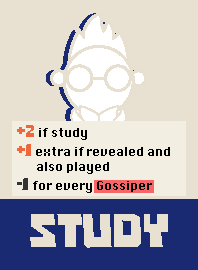

- Spade ♠ - Study

Playing this card means you are doing your work properly. You can get 1 point for that turn.

- Diamond ♦ - Cheat

Playing this card means you are trying to get extra advantages. But there is a risk of being reported by other students.

You can ONLY cheat when you are in a group.

If you cheat in a group with nobody in the group playing Snitch, you will get 2 points with 1 point for every other cheater. For example, if you cheat with 2 of your group members, and no one is playing Snitch, all 3 of you would get 2+1*2=4 points for that turn.

If you are not in a group, playing this card gives you 0 point.

If you cheat with someone playing Snitch in your group, you get 0 point for the turn.

- Club ♣ - Snitch.

Playing this card means you are angry about other students cheating, and you are going to stop it by reporting them to the professor. But in order to collect evidence, you have to be in the group.

You can ONLY Snitch when you are in a group.

If you snitch with some students in the same group playing Cheat, you will get 1 point for every cheater you caught. For example, if you play Snitch when 3 of your group members cheating, you will get 3 points, and the 3 cheaters all get 0.

If you are not in a group, playing this card gives you 0 point.

Playing Snitch is not mathematically optimal, but it could help you catch up with leading players.

- Heart ♥ - Troublemaker

Playing this card means you are happy to see other students fighting against each other. The more chaotic they are, the happier you would be.

If you play Troublemaker, you will get 1 points for each suit except Heart being played this turn. For example, if other players are only playing Study (Spade) and Cheat (Diamond), you will get 2 points.

The maximum you can get for this turn is 3 points, since there are only 3 possible suits beside Heart.\

Winning:

- When every player’s hand is down to one card, the game ends.

- The player with the highest score become the winner. Congratulations! You become the best student (but probably not the best person) in the class!

Design Process

Study Group went through several iterations to get it to its final state. We started with a theme: students preparing for a test, and cheating with other students. We hoped to build the actual gameplay mechanics around that theme, as opposed to building a theme around fun mechanics. In hindsight, this unorthodox approach to game design might’ve hindered our process much more than we had expected.

The first version of the game was focused around questions on a single test. In this iteration, there were literal answers for every question on the 10 part test (multiple choice represented by four suit possibilities). The game would end once every player had submitted the answers to every question on the test in a manner that was similar to werewolf. Players would choose from a mix of options every round:

Study - Look at one of the facedown answers.

Cheat - If no one Snitched you, look at two of the facedown answers.

Snitch - While all heads are down, point at another player. If they Cheat this round, they lose their turn. You then get to look at one facedown answer.

Lastly, there were special roles that would be assigned to the players. Some would be Hackers, able to switch the order of the answers on the test. Others would be Bookworms, able to study more efficiently than the average player. We had several more in this same vein that never reached implementation. In theory, these roles would behave in a similar vein to those of werewolf, adding an extra dynamique to the game on top of ‘cheat’ vs ‘snitch’. In reality, they added surprisingly little diversity. You would always do the action that was the best option. If your ability was too strong, you’d always use it above studying. If it was too weak, you’d never touch it.

Likewise, the actual layout of the test was, in theory, meant to add a concrete visual to the player’s goal. When we tested it, however, it added an unexpected clunkiness and time restraint to the game. Rounds would take longer, as players had to literally check answers and write them down as notes. The additional requirement of paper and pencils, just for the physical test to work, was added excessive overhead to the game’s flow. The game also included routinely having th “teacher” putting each player’s head down to play their action for the round Lastly, this first version was riddled with balancing issues. Perhaps because the actions all had to be tied to physically looking at the cards in some way, it felt impossible to develop them into a unique but equal group of options.

Given the rather inefficient state of that prototype, we tried changing a lot. One of our first decisions was to try throwing away the literal test and transitioning it to an abstraction through victory points. This immediately felt more positive, speeding up the down time of the game. It also meant we could avoid the ‘everyone put your heads down’ phase, as needed in our first prototype. With players gaining abstract ‘test points,’ rather than literal test answers, there was no need to hide any test answers. This also meant we wouldn’t need a Teacher (referee in Werewolf) to narrate and facilitate the game. Every player could play in every round.

Next, we took a hard look at the roles of the players. In games like Werewolf of The Resistance, different roles are interesting in part because they have different goals. In Study Group, however, the only real difference in the roles was their special actions. You’d never care what roles the other players were; all that you actually interacted with was your own role’s power. We experimented with changing the objective of different roles. In one small playtest, we had a hidden ‘snitch,’ whose goal was simply to rat out as many cheaters as possible. Alas, given several constraints (four players, limited tools for a snitch to hide themselves, a lack of reliance on the ‘cheat’ option for other players) this did not work at all. Perhaps, given more time and more experimentation, there was potential in the Snitch role. It would certainly be something to return to, as we never had the chance to try and fix its problem. In the end, we all agreed that the roles were, in their present state, a superfluous system, irrelevant to play. Thus, we decided to remove it.

Finally, the balance issues become much easier to fix as we sped up the round speed. As we removed limitations like putting your heads down, needing a narrator to speak, writing down your answers, we were able to breeze through dozens of small variations on the round structure, avoiding overhead and maintaining flow in the game. We found several small edits that went a far way in helping the game. For one, we added the ‘reveal two, place one’ system. Each player would reveal two of the four cards to the others. Those were their two options. Having seen and considered the others’ cards, a player would choose one of these two to play. This went a far way in removing the element of dumb luck from the rounds and move toward a more of a prisoner’s dilemma type of game. Other changes included moving Cheat from a stagnant ‘2’ to a ‘2 + 1 for every other cheater,’ pressuring you to cooperate with other cheaters. Arguably the most significant addition in this phase was the ‘Swap.’ Represented by the Ace of a card deck, this was the fourth option for the player (Again, the other three being Study, Cheat, Snitch). Swap would allow you to switch another player’s chosen card with their second, neglected choice. The thought process behind Swap was that it would add some additional protection to a Cheat played alongside it (as Swap would coexist with the player’s other choice), allowing you to switch another player’s Snitch. We hoped it would create another layer of mind games, with players wondering if the others had placed their snitches forward or kept them back. This was our prototype of Study Group, and was the version we took to class on Thursday. We knew it was still very rough, but still thought we had made significant progress from the original prototype.

Unfortunately, in our labour to patch the game’s holes we had poked through dozens more. Jesse critiqued the game for a multitude of fresh problems. With the new system, every round was the same and the game lacked landscape. There was no build up, no evolution. Stakes stayed stagnant until the game ended at an arbitrary point. Swap was an inherently poorly designed ability. It shared absolutely no resemblance to the other abilities, didn’t fit the theme, and was simply too strong. Lastly, you had an infinite supply of every option. Players would never be forced out of their comfort zone, or constrained in any way. If you were a conservative or timid player, you’d play the relatively boring Study every round, never experiencing actual gameplay.

In our final approach to fixing this game, we threw dozens of ideas at the wall. Few of them stuck. For Swap, we tried replacing it with several new abilities. We agreed that we needed a fourth option to break up the roshambo aspect, but we couldn’t figure out what that fourth card should actually be. We experimented with it stealing another player’s ability (If they played cheat, it would become a cloned cheat). We tried having it be powerful, but move through the players’ hands as they use it. We tried it as a Sabotage card, ruining another player’s Study. Lastly, we tried it as a card that gave ‘+1 for every other suit played this round.’ This final idea wasn’t necessarily better than any of the previous, but it seemed to be the one with the least problems. Thus, taking the time constraint into consideration, we moved forward with Swap redefined as Diversity.

Other small reworks involved the variety in play and predictability of other players. We added a constraint to the player choice. Now, there was a finite number of cards. Every player got two of each action instead of unlimited. Thus, by remembering another player’s history one could remember if they still had Snitches or Cheats left in their arsenal. This had the bonus side effect of adding a definitive end to the game: once players had run out of cards, the game was over.

Our final change ended up being crucial to Study Group’s redemption. We decided to add one last mechanic to the game: Groups. Now, cheating wouldn’t be a solitary act. You’d have to collaborate with other players, making an official ‘cheat group’ to get any points. The bigger the group, the more potential points. However, there was always the underlying threat that someone had lied to your face, planning to Snitch. By making these Groups form after one card had been revealed (but not the second), we complicated the classic Prisoner’s dilemma structure. You’d know that every other cheater had chosen to bring along the Cheat card; at the very least they were considering cheating. But there was always the risk of that second, hidden card. Had they brought along Cheat just to trick you?

This was the final version of Study Group. It is still a very, very flawed game. Issues include an untested >4 player mode, a too powerful Diversity action, and the underwhelming effect of Study. It could be argued that through the design process we just swapped our problems for new ones. It wasn’t from lack of trying. Perhaps if we had approached in the beginning from a better angle, or maybe backed out once we saw the overwhelming problems, we wouldn’t have ended up falling down this rabbit hole. With more time we would have loved to start from scratch and build a more solid foundation. Still, given our backwards beginnings, it’s to our amazement that what we ended up with had some functionality, balance, and fun.